WORKING FOR WATER (WfW) DEFINED

The main environmental legislation that contains legal obligations relating to alien and invasive species is the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act (NEMBA), 2004 (Act 10 of 2004), a subordinate legislation under the National Environmental Management Act (NEMA), 1998 (Act 107 of 1998), supported by the NEMBA A&IS Regulations, 2020. A host of other environmental legislation under the umbrella of NEMA have relevance to biological invasions. Historically, environmental legislation was guided by various policy documents including the draft White Paper on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of South Africa's Biological Diversity (1997) and the White Paper on Environmental Management Policy for South

Africa (1998). Experiences and lessons learnt from several decades of conserving South Africa's biodiversity has highlighted the need to update these policy documents to address the gaps identified and to clearly outline South Africa's vision for conservation.

The 2023 White Paper on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of South Africa's Biodiversity seeks to do just that, including providing a policy direction in the management of biological invasions. The White Paper on Conservation and Sustainable Use (2023) has a policy objective with the aim to identify and manage harmful, and potentially harmful, invasive alien species, their potential and existing introduction pathways, and biological invasions. This will be done as part of the White Paper's goal to enhance biodiversity conservation.

South Africa's regulations on alien and invasive species are comprehensive, innovative and are becoming effective. These regulations were originally promulgated in 2014 (revised in early 2021), and are increasingly being enforced, with the first successful prosecution in 2019.

In addition, the evidence underpinning the regulatory listing of invasive species is being formalised, and the process for granting permits is functioning well with effective protocols being implemented to regulate the intentional, legal importation of alien species. Biological invasions are amongst the leading causes of global change they have had profound negative impacts on people and nature for centuries; are currently a significant drain on South Africa's sustainable development; are negatively impacting native biodiversity; and pose a major threat to the quality of life of present and future generations and the globally unique flora

and fauna that are an integral part of this country. The problem is complicated and set to grow.

ALIEN SPECIES ESTABLISHED IN SA

At least 1880 alien species have become established in the country, about a third of which are invasive. Invasive species come from many different taxa, invade different habitats, and cause various types of impacts, sometimes in ways which are not yet fully understood but that will have profound effects on the ability of ecosystems to deliver services to people.

STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE

- To assist with reducing the rates and impacts of invasive alien plants in South Africa.

R12 billion

25%

R340 million

15%

The gross financial cost of the damages, where these have been reported, is ~R12 billion every year. The true cost may be as much as ten times this figure. Invasive plants use up 3–5% of surface water runoff each year, and during the 2016–2018 drought in Cape Town, day zero could have been pushed back by two months if the catchments had been cleared of invasive trees. 25% of all biodiversity loss in South Africa is due to biological invasions. Rural livelihoods are threatened by alien plants, with livestock production from natural rangelands reduced by R340 million per year. The extent and severity of damaging wildfires is significantly increased by invasions, e.g., 15% more fuel was burnt in areas invaded by trees than uninvaded areas in the destructive wildfires in Knysna in 2018.

RESOURCES INVESTMENT

Significant resources have been invested to combat biological invasions. Over R1 billion has been spent per year by the government to manage existing plant invasions and create jobs. Over the past 25-years, control operations have been conducted on ~ 76 000 sites, covering 2.7 million ha. However, this is only ~ 14% of the estimated invaded area.

However, there are notable success stories dating back many decades. In the early 1900s farms in the Eastern Cape were completely covered by cactus invasions. The use of classical biological control meant that the land could be farmed again.

Biocontrol continues to be a critical and well-regulated tool to manage biological invasions, with South Africa recognised as a global leader in the field. The use of biological control against invasive alien plants has been shown to have very high positive returns on investment, with benefit: cost ratios that range from 8:1 to ~4000:1.

CATEGORIES OF PROJECTS

IMPLEMENTED WITHIN WORKING FOR WATER

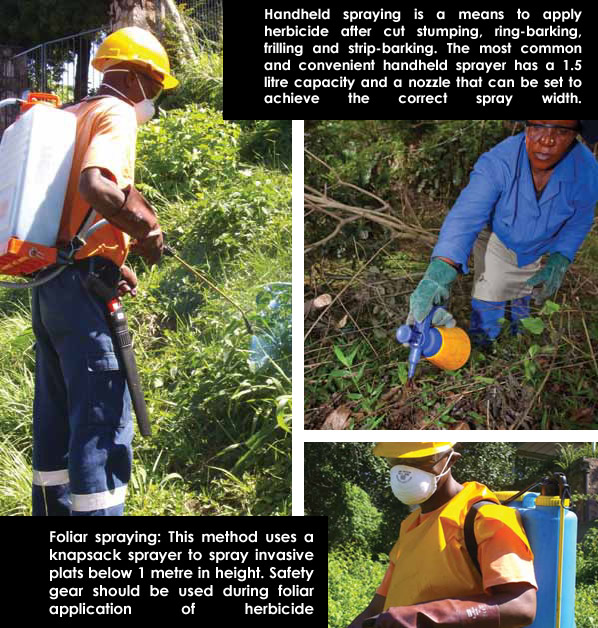

Almost all invasive alien plant species must be cleared mechanically, using chainsaws in some cases, or hand-weeding in others, in combination with the application of herbicides where appropriate. The need for labour-intensive methods provides the opportunity to create employment in impoverished rural areas. The creation of employment and development opportunities, in combination with control efforts has made it possible to secure substantial amounts of funding for these activities and has been the cornerstone of control programmes across the country since 1995.

In order to implement control projects, contracts are awarded to individuals who then clear invasive plants from agreed areas and conduct follow-up work. This system has drawbacks, notably that employment on short-term contracts does not provide a reliable source of steady income and can result in a high turnover of workers; this in turn means that new workers have to be trained each time a new area is subjected to control. The dual goals of job creation and effective control have to be accommodated, in line with the strategy that strives to maximise funding potential through accommodating diverse benefits.

Biological control of invasive alien plants involves the use of agents introduced from the country of origin (plant-feeding insects and mites, and plant pathogens) after rigorous testing under quarantine conditions to ensure that they do not pose a substantial risk to any agricultural crop or indigenous plant species. Release applications are extensively scrutinised. The biological control of invasive alien plants, using plant-feeding insects and mites, and pathogens, is an attractive management option because: (i) it is relatively cheap and very safe compared with the costs and risks associated with herbicide development and deployment; (ii) biological control can be successfully integrated with other management practices; (iii) biological control agents can often (though not always) disperse to and control plants in otherwise inaccessible areas; and (iv), most compelling of all, biological control is self-sustaining. Without biological control, invasive alien plant management would be beyond the capabilities and resources of South Africa. For biological control to be integrated with other control measures it is crucial to understand the impact of the agents. This requires pre- and post-release evaluation of the target plant. This has too often been assigned a low priority, and once an agent was released, researchers were redeployed to work on new agents. Some agents also need to be manually redistributed around the country or repeatedly released for control to be achieved.

Many alien plant species invade areas that are rugged and inaccessible, especially in mountain areas, but these need to be prioritised for control in many cases. Studies have shown that an individual plant on an exposed slope or mountain top can contribute more to increases in the area invaded than do all the plants in a hectare of dense infestation in a lowland, as seeds from a single isolated plant on a mountain top will be dispersed much further and over a wider area. This suggests that plants in inaccessible areas need to be cleared as they would otherwise provide a constant source of seeds that would drive re-invasion of more accessible areas that have been cleared. In order to deal with this problem, the Working for Water programme has trained, equipped and deployed teams of workers to clear cliff faces and other inaccessible areas across the country (so-called “high-altitude teams”). To date there has been no assessment of how effective this approach has been, but high-altitude teams plan and execute tasks independently of other control operations. However, if planned and executed in collaboration with adjacent projects, the approach offers a solution to the problem of dealing with invasive alien plants in inaccessible mountain areas.

The intended outcome for emerging weed control is the identification and assessment of newly established invasive alien species, or species with limited distributions, and eradication of species where feasible and desirable.

The Eco-Furniture Factories Programme seeks to make optimal use of some of the biomass cleared by Working for Water in creating work opportunities to make products that help Government to meet its needs, and notably the pro-poor opportunities within this. Five Eco-Furniture Programme factories have been established. The programme makes products that government needs from wood obtained from the clearing of invasive alien trees. The programme also intends to promote the general use of biomass through biogas digesters, in providing energy and jobs to the rural poor. In addition, there is potential to use wood chips from invasive trees and shrubs to make wood-wool cement board fibre, which might be highly competitive in dealing with the need for housing, and other buildings. All these interventions are politically attractive, as they address multiple needs. Their potential to enlarge the pool of funding available for managing biological invasions is substantial.

The intended outcome of aquatic weed control is preventing the erosion of, or restoring, ecosystem services, biodiversity, and ecological integrity in freshwater ecosystems. Water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), a South American aquatic weed introduced widely into Africa, has blocked waterways limiting boat traffic, access to safe water and fishing. Water hyacinth also blocks sunlight and oxygen, dramatically altering biological diversity in aquatic ecosystems.